“The problem is how to deal with the 160 million people with employer coverage. Telling them that they have to give that up, but don’t worry, our plan will be better still looks unrealistic. It’s about loss aversion: hard to convince people to fix something they don’t see as broken.”

- Paul Krugman

Answer: People don't really care about their insurance company; they care about losing their doctor or their benefits. Since Medicare for All actually expands the provider network and benefits beyond the scope of any employer or private insurance, coverage could only be gained - not lost.

Much of the concern about “loss aversion” is based on polls that show Americans are reluctant to give up their private employer coverage. These polls have a major flaw: they tell respondents that under Medicare for All they would lose their private plan, but don't specify what M4A would cover (e.g. no cost-sharing, no networks, comprehensive benefits). The only thing we can conclude from this data is that people are afraid of losing what they have for an unknown benefit.

This issue can be illuminated by considering the following questions: Do people care about the brand name on their insurance card, or do they care about being able to see the doctor they want and have their procedures and prescriptions covered? When their employer switches from one insurance company to another, does the employee really care about to which company, or do they care about how their network and costs change?

Satisfaction with health insurance hinges on access, not brand name. And polling shows that when it comes to insurers, Americans don't trust private companies. A 2017 poll shows that only 16% of Americans believe that private health insurers put patients over profits. And patients with public insurance report higher satisfaction rates than those with private insurance.

Background on Democratic Healthcare Polling

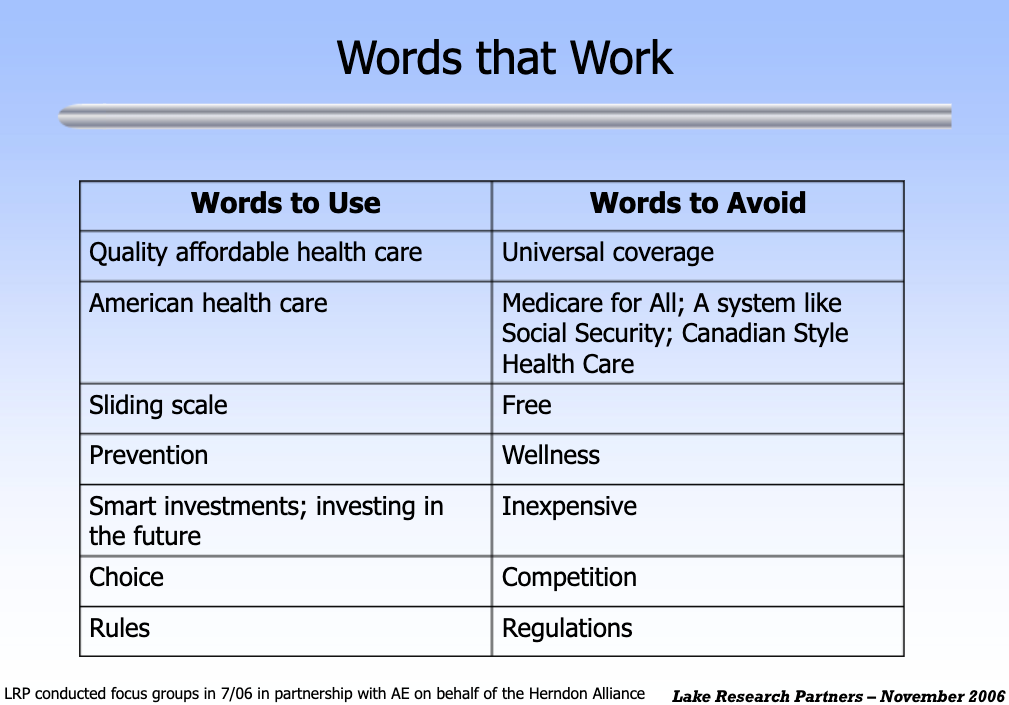

Suspect polling has been used to compromise the fight for universal healthcare for years. In 2007, prominent Democratic pollster Celinda Lake published research arguing that Americans are quite conservative on healthcare. Ideas invoking “government solutions” were losers, while “choice”, according to Lake, polled well. This research dictated Democratic messaging on healthcare for years after; it determined what was considering politically possible and shaped the trajectory of the Affordable Care Act.

Lake warned against using the term “universal coverage” because her polling showed that Americans are “opposed to helping those perceived as undeserving” and want an “American solution.” Similarly, the term “Medicare for All” was a no-go, with the preferred messaging “American Health Care”.

Lake warned against using the term “universal coverage” because her polling showed that Americans are “opposed to helping those perceived as undeserving” and want an “American solution.” Similarly, the term “Medicare for All” was a no-go, with the preferred messaging “American Health Care”.

6 years after this report was published, both Obama and Clinton ran on "universal healthcare". Today, her recommended Words to Avoid are embraced by almost every Democratic politician; it’s hard to find a Democrat who doesn’t stand behind “the goal of universal coverage”, and almost every new healthcare proposal from the party has the term “Medicare” in its title.

Meanwhile, the last “American Health Care” plan came from the GOP (the American Healthcare Act of 2017).

Lake's polling wasn't only wrong; it encouraged Democrats to take policy positions based on polling rather than the moral imperative of fulfilling every person's right to health care.