Universal Healthcare is Public Healthcare

Media, pundits, and legislators claim we can "build on the current system" to achieve universal healthcare coverage, and that there are "multiple pathways" which don't require eliminating for-profit, employer-based insurance. Proponents often cite European countries like Switzerland, Germany and the Netherlands as examples of countries that have achieved universal coverage without single payer.

The truth is that none of our peer countries have achieved universal healthcare through a private, for-profit insurance system. Most high-income countries run single payers; the ones that do not rely on sickness funds or other quasi-public institutions rather than private insurers. This project looks more closely at those healthcare systems and examines how exactly they provide universal coverage for their residents.

Most European Countries Have Single Payer

Most of the 35 countries in the European Union and the Schengen agreement have single payer healthcare systems. And in every country but Slovakia, primary coverage is provided by public or quasi-public entities.

Supplemental insurance (or "top-up" insurance) is sold in almost every healthcare system, and is sometimes delivered by profit-making entities; but because it covers so little (typically copays, extra costs for vision and dental treatments, or "extras" like a private hospital room) it's a very small percentage of overall health spending, generally at 5% or less. See our Citations.

27 countries run single payer systems

6 other countries, including Switzerland and Germany, allow sickness funds or quasi-public entities to provide primary health coverage

1 country allows for-profit insurers to provide primary coverage: Slovakia

Private Insurers Can't Deliver Universal Care

Except Slovakia, all of Europe uses public or quasi-public entities to administer the government's healthcare plan.

Belgium, Germany, Switzerland, Netherlands, & Czechia use quasi-public insurers that are or were formerly sickness funds.

The following features differentiate them from truly private entities:

- GOVERNMENT MANAGES RISK

- Corporate insurers (Aetna, Cigna), and even private, non-profit insurers (Blue Cross) - take on risk. They have an incentive to recruit for and select healthy, inexpensive customers. With public insurers, risk is largely managed by the government through central risk pooling. Funds are pooled and redistributed according to the risk profile of each insurers' members. Pooling risk is essential to the stability and incentives of the system; this is why every European country pools risk across insurers. Pooling also removes the incentive to cherry-pick.

- PROFITS ARE ILLEGAL

- Private insurers are free to make a profit off the business of health insurance; public insurers are outlawed from profit-making on standard coverage.

- COMPETITION IS LIMITED

- Private insurers make operating decisions like what to cover and for how much. Most working Americans are covered by self-insured private plans, which are exempt from many federal regulations (including key parts of the ACA). Public and quasi-public insurers, on the other hand, are largely constrained by a nationally-set benefits package and fee schedule which makes coverage equitable and uniformly comprehensive.

Public Regulation - not Private Competition - Controls Costs

In addition to the regulations on insurers, the following system-wide cost controls are standard in Europe:

-

-

-

- Physicians are paid according to a fee schedule (or salary level) negotiated nationally

- Hospital care is also largely reimbursed through standardized rates (DRGs), almost always negotiated nationally

- Pharmaceutical prices are negotiated and set nationally

- Nationally-determined spending caps on hospital care, or global budgeting of hospitals/the health system

- Mark-ups for pharmaceuticals are regulated at both the retail and wholesaler level

- Physicians are paid according to a fee schedule (or salary level) negotiated nationally

-

-

Providing everyone with care that is truly comprehensive and continuous from cradle to grave requires strict control of costs at the national level. Universal coverage is unsustainable without government planning.

What it will take to move us to a Dutch or German system?

None of the incremental reforms currently proposed in the U.S. Congress would get us to even the imperfect Dutch healthcare system - where 80% of all health expenditure is public.

To transition to the Netherlands system, here are some steps we'd need to take:

Step 1: Institute a payroll tax to cover 50% of the insurance plan. Flat premiums of around $120 per month would also be instituted, accounting for 45% of total spending. About 57% of households will receive subsidies to help cover this cost, to be funded through a different tax.

Step 2: Budget for and finance long-term care nationally, through taxation

Step 3: Cover all children through fully-public funds

Step 4: Institute a fixed annual growth rate set for hospitals, primary care, and other sectors, set by the Minister of Health

Step 5: Prevent insurers from making profits on the statutory package, requiring them to:

- Accept government redistribution of their funds

- Cover everything in the state-determined benefits package

- Provide primary care as free at point of delivery

- Abide by maximum prices set by the state

- Abide by their budget, which is set by the Health Minister

None of the incremental reforms currently proposed in the U.S. Congress would get us to even the imperfect German healthcare system.

To transition to the German system, here are some steps we'd need to take:

Step 1: Institute a payroll tax for payment of the plan, collected by the state, which redistributes the resources to the funds according to the risk profile of their members

Step 2: Budget for and finance long-term care nationally, through taxation

Step 3: Institute a fixed annual growth rate set for hospitals, set by the Minister of Health

Step 4: Convert our for-profit & private health insurers to non-profit sickness funds, requiring them to:

- Transfer all their funds to the Central Reallocation Pool, to be redistributed

- Cover everything in the state-determined benefits package; prior authorization is prohibited

- Charge a maximum copay of 10 euro for most care including outpatient visits, inpatient (per day), prescription drugs, rehab, and emergency care.

- Abide by maximum prices set by the state

- Abide by their budget, which is set by the Health Minister

Single Payer Systems are the Fairest & Most Efficient

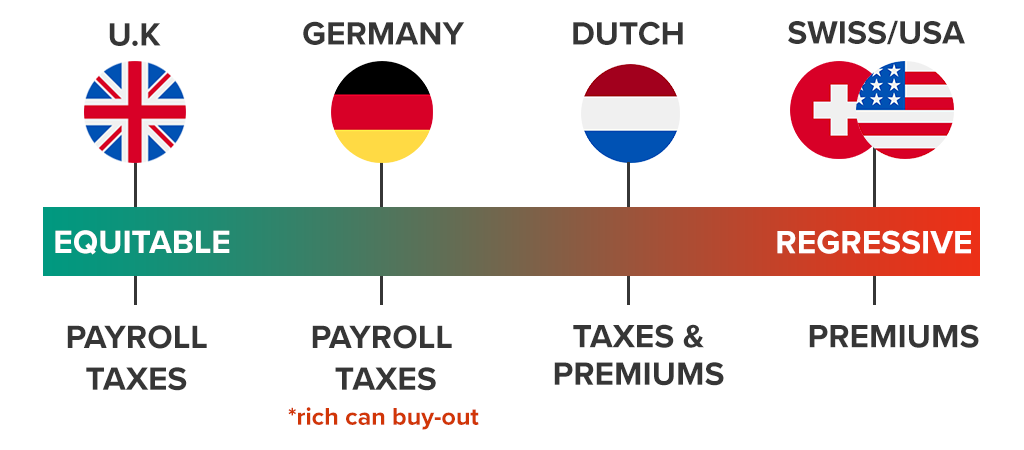

Multipayer systems aren't just less efficient and more costly; they're also regressively financed.

Progressive income taxation ensures that people pay according to their means. A monthly premium system, which requires people to pay the same amount for the same product regardless of their income, means that a middle class family will spend significantly more of their income on healthcare than, for example, Jeff Bezos or Bill Gates.

This is a snapshot of how various EU healthcare systems are financed:

United Kingdom: payroll-based financing system; patients pay a fixed percentage of their income

Germany: payroll-based system; but wealthier patients can opt-out from the system to buy private insurance

The Netherlands: 50% of the insurance system is financed through progressive payroll taxation. The other 50% is financed through flat, regressive premiums. Subsidies and spending caps apply for the lowest income, but lower-middle and middle class patients are disproportionately burdened while wealthier patients pay much less of their household budget for care.

Switzerland: Health insurance is largely financed through flat, regressive premiums. Subsidies and spending caps apply for the lowest income, but lower-middle and middle class patients are disproportionately burdened while wealthier patients pay much less of their household budget for care; in 2016, 22% of the Swiss population reported going without needed health care because of costs, with this rate being particularly high among people with low-income (31%).

The premium payment system is not only wasteful and adds needless administration; it also provides another avenue for insurers to cut off care.

"Medicare For Some": Neither Universal Nor Sustainable

"Medicare for some" bills tinker around the edges of for-profit multipayers and don't include strong national regulation on spending.

Several pieces of legislation have been introduced recently, all purporting to achieve universal healthcare. Almost all of them retain the current system of for-profit insurers, and only the Medicare for All bills actually institute nationwide regulation on spending.

| Universal Coverage? | Must be nonprofit? | National Provider Rates? | National Drug Pricing? | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 34 European Countries |  |  |  |  |

| Medicare for All |  |  |  |  |

| Public Option | ||||

| Medicare for America |

Only a National Medicare for All Can Prevent Unnecessary Deaths

Under a premium payment system (rather than a tax-funded system), if you fail to pay every month - or if the insurer makes an error - your coverage can be cut off at any time. When Danny Desnoyers missed a $20 Medicaid premium (a private insurer was running his plan), they dropped his coverage and he was left without his expensive anti-depressant. After rationing for a couple weeks, he completely ran out and shortly after committed suicide.

Imagine if our public education system was financed like our healthcare system. If you couldn't or forgot to pay your monthly premium, your children wouldn't go to school that month. During periods of unemployment or a strained household budget, they might go months or even years missing education. That's exactly how our healthcare system works.

Most countries never allow this to happen; they guarantee cradle to grave coverage by financing their healthcare systems through taxation independent of a patient's employment status or wage.

Medicare for America and public option plans allows the abuses in the current system to continue by preserving private entities' management of healthcare access. Only a taxpayer-funded plan would ensure continuous, irrevocable coverage, including during times of financial distress - the times one may most likely need a guarantee of healthcare.